Mar 24, 2023

By Rick McNary

Have you ever had an idea grab hold of you so tight, it just will not let go? You think about it, research it, ask other people about and try to let it go, but it just keeps hanging on? Then you try to make the idea come to reality and you get great traction, then, poof, it is gone? But you cannot quite give it up, so you wait. And wait. And wait.

Then poof! It takes off like a rocket and you are strapped in tight, excited for the ride but barely able to hang on. That is what happened to me. It all started 12 years ago in a simple conversation at a conference when I asked a simple question, and the answers lit a fire in me that has never gone out.

The idea? How could I bring a rural community together around the production, processing and distribution of food raised locally in such a way that it prospered established businesses and started new ones plus, created unity in the community.

I wondered how I could connect people like me who do not farm to those who do so they could sell directly to consumers. Here is the backstory.

Working in the international hunger space

I had been involved in international hunger since a starving 5-year-old girl in Nicaragua asked me to feed her. I have always enjoyed engaging others in good causes, so I started a nonprofit in El Dorado to engage volunteers in meal packaging events where people of any ages and skills could package dry ingredients into a quart size bag (rice and beans, for example) then seal it up, box it and send it to hungry people. A friend of mine, Jolynn Berk, came up with the name, “Numana.” Like the Bible story of manna falling from heaven, only this was new – ergo, Numana.

In September of 2009, we had $209.39 in the account, and I told my wife we needed to either jump headlong into it or walk away from it. I quit my remodeling business and jumped headlong into it.

Three months later, on December 29 and 30, 2009, we had our first packaging event to send a 40-foot container filled with 285,120 meals to Salvation Army in Haiti for the 13,000+ kids in their schools. Two weeks after we packaged the meals, that horrible earthquake hit Haiti. Col. Starrett of the Salvation Army sent in a KC 135 to pick up all those meals, then let us know they air-dropped them into Haiti since the airport was destroyed.

My wife pointed out that the first box of Numana we ever packaged fell from the sky to hungry people. You cannot make that stuff up!

In the next six months, we ended up packaging 20 million meals in various Salvation Army locations across America and engaged more than 120,000 volunteers. By September of 2010, we had grossed more than $5 million. That is a big step from $209.39 the previous year.

Local food systems

I was at an agricultural conference in 2011 because I realized that after 10 years of working in international hunger relief (give a person a fish) and development (teach a person to fish) programs that if I was serious about ending hunger, I needed to understand and support agriculture. Even though I grew up in rural Kansas, I had no idea how farmers and ranchers conducted their businesses.

It was a comment made to me by the mayor of an old village in Colombia, South America, that started my interest. I had sent a million meals worth of food aid to their country after torrential rains had wiped out farms and went down to inspect it afterwards.

As we were walking along the cobble stones of the street between homes made of adobe with wrought iron windows and bougainvillea cascading off the roof, he pointed to the farmers along the hillsides of the Andes and said, “Without them, we die.” I knew then that I had to learn about agriculture.

At that ag conference, I asked this question, “I see the signs along the highway that read Kansas Farmers Feed 155 People + You, but how does that work? I have lived around farms all my life and have never bought one thing from them.”

The director of Kansas State University’s food science department, Dr. Curtis Kastner, began to explain the rising interest of direct-to-consumer sales both from the side of the farmer/rancher as well as the consumer wanting to buy local. Then what he explained to me next is what got me started on this big idea that has not let me go.

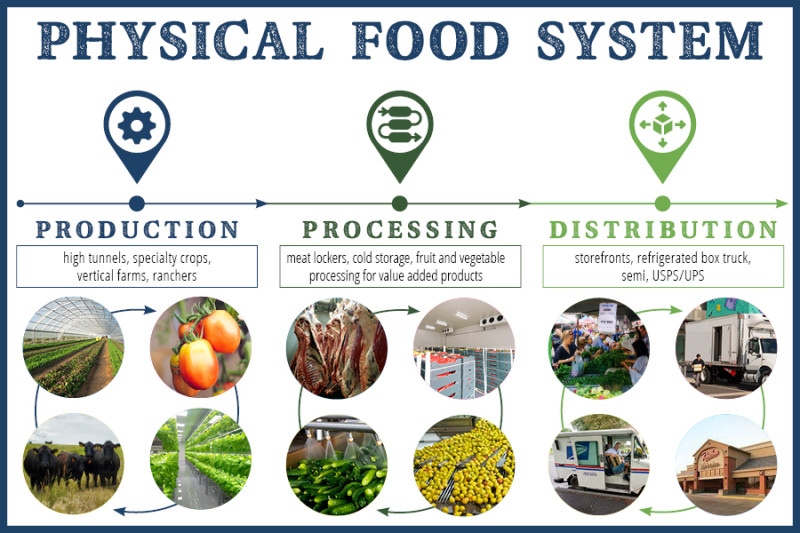

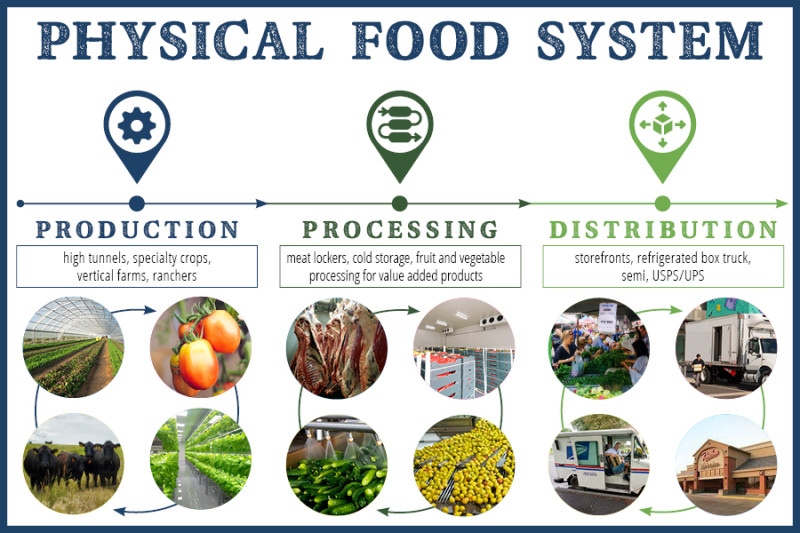

He asked me if I knew what a local food system was, and I shook my head no. He explained that a food system is made up of three basic parts: production – growing a plant or animal for human consumption; processing – taking that plant or animal and getting it read for human consumption; distribution – all the steps involved getting the processed items to the plate for human consumption.

He went on to say that he was on Janet Napolitano’s department of Homeland Security’s board, and they were extremely interested in how to create local food systems as back up and resilient plans in case the global food system ever broke down. They were concerned about bioterrorist interruptions to our food system’s supply chains and were interested in supporting models for local and regional food systems.

That is when the big idea that grabbed me and would not let me go. I spent a lot of time with K-State faculty trying to understand what I could do to start one in n El Dorado. I got involved in local food systems conversations in Washington, D.C., through my connections with the Alliance to End Hunger. At the time, the Alliance had been given the Hunger Free Communities Network (HFCN) model developed by the Secretary of Agriculture during his first term, Tom Vilsack. The Alliance and HFCN were looking for models to support, too.

So, we wrote a model that involved building out all three of those components in El Dorado. I met with various city and county government leaders and was making great headway on the model. The city gave us access to 27 acres of land that they owned but could not do much with but were perfect for starting community gardens and orchards. There was a local meat locker so processing meat was available, but we needed cold storage for vegetables and fruits as well as some type of small-scale commercial processing.

Typically, vegetables and fruits are only grown during certain seasons in Kansas which also means they are only available during those seasons at farmers markets. However, if you can add cold storage for extending their life as well as a commercial kitchen to take those products and make shelf-stable items like canned beans, salsas, tomato sauces and the like, you suddenly have a year-round and possibly a nation-wide market for those shelf-stable products. But you need a certified commercial kitchen which are not cheap. So, we were looking at building a kitchen we could lease to food entrepreneurs who had secret family recipes and a desire to make a product they could sell, but just did not have the capacity to build their own kitchen.

We called our model, Numana Gardens. We won third place for a national innovation model. My big idea was, pun intended, taking roots.

We were making great traction then a day came when I, and all our staff at Numana, were terminated in an email. That big idea went “poof.” That was 2012.

But that big idea would not let me go. Sometimes I could go days without thinking about it, but then it would sneak back in and kiss me when I was not looking. It was such a sweet idea.

I continued researching, reading, writing and dreaming about starting it, but nothing ever happened. There was a lot more national and international interest, a lot more articles were being written, a lot of nonprofits and government agencies were working on them, but I just could not find my place in that space. Oh, I tried, but you know, square pegs, round holes.

Digital food hubs

I noticed gaps in all the food systems work I saw happening. Although I have been in nonprofit work most of my life, I am an entrepreneur at heart. And entrepreneurs see gaps.

One of those gaps was a need for a digital hub to connect those three components of production, processing and distribution. But a digital hub means a website and websites are thousands of dollars.

I continued to wait and talk to anybody that would listen about the opportunities for both business development and community engagement in a local and regional food system. But I was busy doing the international hunger programs in a different capacity and did not have the time or the resources to pursue my big idea.

Then the pandemic hit in 2020 and suddenly Dr. Kastner’s concern about the fragile nature of our global food system became apparent as supply chains were interrupted and meat counters were empty at the local grocery store.

Along that journey into understanding farmers and ranchers, I had approached Kansas Farm Bureau with the idea I could write feature stories about their members as an outsider looking in. I began that delightful journey in 2015 and have met the most wonderful farm and ranch people in the world who have become my heroes. I have drunk coffee with them around their dining room tables when it is still dark outside, bounced along in their trucks as they showed me their fields and livestock, and even had to wipe a bit of barnyard off my boots on occasion. I met many who were starting to sell direct to consumers.

The start of Shop Kansas Farms

When the pandemic hit, and my wife told me the meat counter at the grocery store was empty - right after we had dined on great beef purchased from a local ranch couple - I wondered if I could somehow connect people I knew to the wonderful farm and ranch families of Kansas so they could purchase the food they raise. I grabbed my laptop while I was reclined in my easy chair and started the Facebook group, Shop Kansas Farms. I reached out to farms I knew who sold to consumers and asked them to post their offerings, then I invited some friends and family to join the group. I made the group public so anyone could join if they followed the rules. (That is a whole ‘nother chapter!)

The group grew to 5,000 in the first 24 hours. By the third day when we reached 13,000 members, I realized I had created a digital hub to a regional food system. The group continued to grow to 50,000 in the first week and now, in 2023, has more than 170,000 members.

If you look at Shop Kansas Farms Facebook group postings – and there have been tens of thousands of them – you will see there is an active regional food system connecting to production, processing and distribution.

Looking back, it was God that gave me that big idea and would not let me go. Oh, sure, in typical fashion with God, nothing happens overnight (until he is ready for it too), and there just must be some hard lessons involved, but I am convinced He gave me the idea, then He gave me the ability to make walk it out.

Since I am a person of faith, stewardship is important for me. I have been given talents and gifts by God, but it is my responsibility to take those and improve on them. I am to “be fruitful and multiply.”

Once I understood I had been gifted with a regional food system, then the privilege and responsibility fell upon me to build it out to the best of my ability. It was a stewardship issue.

From the beginning, my friend (and editor of all those articles for Kansas Farm Bureau), Meagan Cramer, saw the distress of those 5,000 joining the first day and all the chaos that came with it, so she and Nancy Brown offered to help. I felt like a little kid walking in front of a dam, seeing a plug and wondering, “what happens if I pull this?” I pulled it and the dam broke. They jumped in a life raft, plunged into the turbulent flood and rescued me; I was drowning.

I had been given a gift of this exciting explosion as well as trusted friends like Meagan, Nancy, Olivia Fletcher, Darrell Peterson, Jr., Katie Carothers and Megan Gilliland to help with administration of the Facebook group.

Along the way, consumers were asking for a searchable map so they could find the farmers near them without having to scroll through the Facebook group so, with stewardship in mind, my wife and I decided to invest our own money and start Shop Kansas Farms, LLC. Although I had some folks suggest, and even some offer, to help me start it as a nonprofit, after what happened to me at Numana, I am not sure God himself could convince me to go that route.

Plus, I have learned in 20-plus years of international hunger relief the best way to end hunger is to have a good job. That was another gap I saw in food systems work; they died when the grant money ran out.

But entrepreneurs drive innovation and innovation drives commerce and commerce produces jobs and incomes.

As time went by, I slowly began to realize my big idea was too big for me to handle alone. One of my favorite authors is John Maxwell who writes, “If you have a vision, the people and the resources will come along to make it happen.”

Shop Kansas Farms and Kansas Farm Bureau

My wife and I spent a lot of time discussing what that looked like and finally decided to offer it for sale to our friends at the Kansas Farm Bureau. When I approached the CEO, Terry Holdren, and Meagan Cramer, the director of communications, who knows Shop Kansas Farms inside and out, they were surprised.

We met again after they discussed it and said they were interested in it, but only if I would agree to hang around as a consultant for at least five years. While I secretly wanted that to happen, it was never a part of what I offered or asked for. Of course, I wanted to hang around!

They were interested in it for three reasons, all three of which are my passion:

- The website with map: It helps farms find new customers and consumers find farmers.

- The Market of Farms: We had the first one in March 2022 in Lyons and had 42 vendors and more than 1,400 people arrived. As one farmer said, “to buy and not to browse.”

- Building a community around food: The regional food system model.

Once the purchase went through, we have been working hard on building out all three of those models and the new website went live on March 21 which is also National Ag Day!

Building a local food system

Back to my big idea of a food system. When Lyons approached me about having a Market of Farms, I asked if they could gather key stakeholders in the community to listen to my big idea about a local food system. Stacy Clark, economic development director; Karly Fredrick, Central Kansas Community Foundation; and Chad Buckley, city administrator, not only listened, but also started leading people through the actions of my model.

Within a year’s time, they have secured a $143,000 USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) grant and have formed a nonprofit, The Harvest Hub. The local Rice County Farm Bureau President, Chad Hook, is the president of Harvest Hub.

The next step is to help other communities build a community around food using the basics of the model I developed which has been refined by the Kansas Farm Bureau.

So, there you have it; finally, after 12 years of dreaming, scheming and sometimes screaming while I pulled my hair out, I get to work every day on my big idea and the beauty of it, is the big idea, can become anyone’s big idea, too. In fact, it will not work unless it does become their big idea, like the Kansas Farm Bureau, Stacy, Karly, Chad and Chad, and all the great people in Rice County who are taking my big idea and making it their really, really, big idea and a big deal.

Turning big ideas into reality

I have learned a few things about myself through the years when it comes to big ideas and maybe these can help you with yours:

- Commit, then figure it out. You must take risks with big ideas, or they just will not happen.

- Make sure your big idea requires the engagement of people who see how it can become their idea and help them in their vocation or avocation. That is how you get buy in. People must understand, like Rice County’s Harvest Hub, why it is good for them, personally and for their community. The Harvest Hub is not doing this for Rick McNary’s big idea; they are doing it for their community.

- Make sure your big idea ultimately helps people who are struggling. Whether it was feeding people through meal packaging events (I went on to spend 10 years with The Outreach Program and engaged others to package even more meals) or helping rural communities who are struggling to keep people and businesses afloat, my ideas are always geared to helping people and communities who are struggling.

Do you want to take our big idea and add your panache to it to make it your big idea?

We can help you. That is what we are here for. To guide you through the process of taking a big idea, adding your creative touches to it and making it a reality for your community.

“It only takes a spark to get a fire going, and soon, all those around, will warm up to its glowing.” (From a camp song I sang as a kid)